| ||

|

Prievous:

| ||

|

Next:

| ||

|

Beginning:

End:

| ||

|

Out-Come:

| ||

|

Place's:

| ||

|

Major Battle's / Campaign's:

| ||

| ||

|

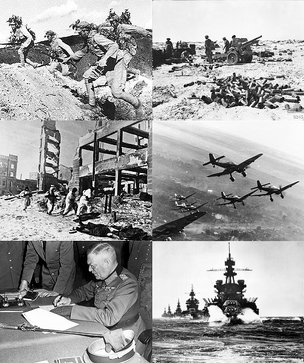

World War II, or the Second World War (often abbreviated as WWII or WW2), was a global Military conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, which involved most of the world's nations, including all of the great powers: eventually forming two opposing military alliances, the Allies and the Axis. It was the most widespread war in history, with more than 100 million military personnel mobilised. In a state of "total war," the major participants placed their entire economic, industrial, and scientific capabilities at the service of the war effort, erasing the distinction between civilian and military resources. Marked by significant events involving the mass death of civilians, including the Holocaust and the only use of nuclear weapoms in warfare, it was the deadliest conflict in human history, resulting in 50 million to over 70 million fatalities.

The war is generally accepted to have begun on 1 September 1939, with the invasion of Poland by Germany and Slovakia, and subsequent declaration of war on Germany by France and most of the countries of the British Empire and Commonwealth. Germany set out to establish a large empire in Europe. From late 1939 to early 1941, in a series of campaigns and treaties, Germany conquered or subdued much of continental Europe; amid Nazi-Soviet agreements, the nominally neutral Soviet Union fully or partially occupied and annexed territories of its six European neighbours. Britain and the Commonwealth remained the only major force continuing the fight against the Axis in North Africa and in extensive naval warfare. In June 1941, the European Axis launched an invasion of the Soviet Union, giving a start to the largest land theatre of war history, which, from this moment on, was tying down the major part of the Axis military power. In December 1941, Japan, which had been at war with China since 1937, and aimed to dominate Asia, attacked the United States and European possessions in the Pacific Ocean, quickly conquering much of the region.

The Axis advance was stopped in 1942 after the defeat of Japan in a series of naval battles and after defeats of European Axis troops in North Africa and, decisively, at Stalingrad. In 1943, with a series of German Defeats in Eastern Europe, the Allied Invasion of Facist Italy, and American victories in the Pacific, the Axis lost the initiative and undertook strategic retreat on all fronts. In 1944, the Western Allies invaded France, while the Soviet Union regained all territorial losses and invaded Germany and its allies.

The war in Europe ended with the capture of Berlin by Soviet and Polish troops and the subsequent German unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945. The Japanese Navy was defeated by the United States, and invasion of the Japanese Archipelago ("Home Islands") became imminent. The war in Asia ended on 15 August 1945 with the surrender of Japan.

The war ended with the total victory of the Allies over Germany and Japan in 1945. World War II altered the political alignment and social structure of the world. The United Nations (UN) was established to foster international cooperation and prevent future conflicts. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged as rival superpowers, setting the stage for the Cold War, which would last for the next 46 years. Meanwhile, the influence of European great powers started to decline, while the decolonisation of Asia and Africa began. Most countries whose industries had been damaged moved towards economic recovery. Political integration, especially in Europe emerged as an effort to stabilise postwar relations.

Invasion of Poland[]

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War (Polish: Kampania wrześniowa or Wojna obronna 1939 roku) in Poland and the Poland Campaign (German: Polenfeldzug) in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, theSoviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe. The invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and ended on 6 October 1939 with Germany and the Soviet Union dividing and annexing the whole of Poland.

The morning after the Gleiwitz incident, German forces invaded Poland from the north, south, and west. As the Germans advanced, Polish forces withdrew from their forward bases of operation close to the Polish-German border to more established lines of defence to the east. After the mid-September Polish defeat in the Battle of the Bzura, the Germans gained an undisputed advantage. Polish forces then withdrew to the southeast where they prepared for a long defence of the Romanian Bridgehead and awaited expected support and relief from France and theUnited Kingdom. The two countries had pacts with Poland and had declared war on Germany on 3 September, though in the end their aid to Poland in the September campaign was very limited.

The Soviet Red Army's invasion of Eastern Poland on 17 September, in accordance with a secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, rendered the Polish plan of defence obsolete. Facing a second front, the Polish government concluded the defence of the Romanian Bridgehead was no longer feasible and ordered an emergency evacuation of all troops to neutral Romania. On 6 October, following the Polish defeat at the Battle of Kock, German and Soviet forces gained full control over Poland. The success of the invasion marked the end of the Second Polish Republic, though Poland never formally surrendered.

On 8 October, after an initial period of military administration, Germany directly annexed western Poland and the former Free City of Danzigand placed the remaining block of territory under the administration of the newly established General Government. The Soviet Unionincorporated its newly acquired areas into its constituent Belarusian and Ukrainian republics, and immediately started a campaign ofsovietization. This included staged elections, the results of which were used to legitimize the Soviet Union's annexation of eastern Poland. In the aftermath of the invasion, a collective of underground resistance organizations formed the Polish Underground State within the territory of the former Polish state. Many of the military exiles that managed to escape Poland subsequently joined the Polish Armed Forces in the West, an armed force loyal to the Polish government in exile.

Prelude to the Campaign

In 1933, the National-Socialist German Workers' Party—under its leader Adolf Hitler—came to power in Germany. Germany sought to gainhegemony in Europe, and to take over territory from the Soviet Union, acquiring "Living Space" (Lebensraum) and expanding "Greater Germany" (Großdeutschland), to be eventually surrounded by a ring of allied states, satellite or puppet states. As part of this long term policy, at first, Hitler pursued a policy of rapprochement with Poland, trying to improve German–Polish relations, culminating in the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934. Earlier, Hitler's foreign policy worked to weaken the ties between Poland and France, and to manoeuvre Poland into the Anti-Comintern Pact, forming a cooperative front against the Soviet Union. Poland would be granted territory of its own, to its northeast, but the concessions the Poles were expected to make meant that their homeland would become largely dependent on Germany, functioning as little more than a client state. The Poles feared that their independence would eventually be threatened altogether.

In addition to Soviet territory, the National-Socialists were also interested in establishing a new border with Poland because the Germanexclave of East Prussia was separated from the rest of the Reich by the "Polish Corridor". The Corridor constituted land long disputed by Poland and Germany, and inhabited by both groups. The Corridor became a part of Poland after the Treaty of Versailles. Many Germans also wanted the city of Danzig and its environs (together the Free City of Danzig) to be reincorporated into Germany. Danzig was an

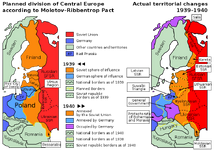

Vyacheslav Molotov signs the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a German–Soviet non-aggression pact.

important port city with 95% of the population German speakers. It had been separated from Germany after Versailles and made into a nominally independent Free City of Danzig. Hitler sought to reverse these territorial losses, and on many occasions made an appeal to Germannationalism, promising to "liberate" the German minority still in the Corridor, as well as Danzig.

Poland participated in the partition of Czechoslovakia that followed the Munich Agreement, although they were not part of the agreement. It coerced Czechoslovakia to surrender the region of Český Těšín by issuing an ultimatum to that effect on 30 September 1938, which was accepted by Czechoslovakia on 1 October.

By 1937, Germany began to increase its demands for Danzig, while proposing that a roadway be built in order to connect East Prussia with Germany proper, running through the Polish Corridor. Poland rejected this proposal, fearing that after accepting these demands, it would become increasingly subject to the will of Germany and eventually lose its independence as the Czechs had. Polish leaders also distrusted Hitler. Furthermore, Germany's collaboration with anti-Polish Ukrainian nationalists from the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which was seen as an effort to isolate and weaken Poland, weakened Hitler's credibility from the Polish point of view. The British were also aware of the situation between Germany and Poland. On 31 March, Poland was backed by a guarantee from Britain and France which stated that Polish territorial integrity would be defended with their support. On the other hand, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, still hoped to strike a deal with Hitler regarding Danzig (and possibly the Polish Corridor), and Hitler hoped for the same. Chamberlain and his supporters believed war could be avoided and hoped Germany would agree to leave the rest of Poland alone. German hegemony over Central Europe was also at stake.

With tensions mounting, Germany turned to aggressive diplomacy as well. On 28 April 1939, it unilaterally

Planned and actual divisions of Poland, according to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, with later adjustments

withdrew from both the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934 and the London Naval Agreement of 1935. Nevertheless, talks over Danzig and the Corridor broke down and months passed without diplomatic interaction between Germany and Poland. During this interim, the Germans learned that France and Britain had failed to secure an alliance with the Soviet Union against Germany and the Soviet Union was interested in an alliance with Germany against Poland. Hitler had already issued orders to prepare for a possible "solution of the Polish problem by military means"—a Case Whitescenario.

However, with the surprise signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August, the denouement of secret Nazi-Soviet talks held in Moscow, Germany neutralized the possibility of Soviet opposition to a campaign against Poland and war became imminent. In fact, the Soviets agreed to aid Germany in the event of France or the UK going to war with Germany over Poland and, in a secret protocol of the pact, the Germans and the Soviets agreed to divide Eastern Europe, including Poland, into two spheres of influence; the western ⅓ of the country was to go to Germany and the eastern ⅔ to the Soviet Union.

The German assault was originally scheduled to begin at 04:00 on 26 August. However, on 25 August, the Polish-British Common Defence Pact was signed as an annex to the Franco-Polish Military Alliance. In this accord, Britain committed itself to the defence of Poland, guaranteeing to preserve Polish independence. At the same time, the British and the Poles were hinting to Berlin that they were willing to resume discussions—not at all how Hitler hoped to frame the conflict. Thus, he wavered and postponed his attack until 1 September, managing to in effect halt the entire invasion "in mid-leap".

However, there was one exception: in the night of 25–6 August, a German sabotage group which had not heard anything about a delay of the invasion made an attack on the Jablunkov Pass and Mosty railway station in Silesia. On the morning of 26 August, this group was repelled by Polish troops. The German side described all this as an incident "caused by an insane individual" (see Jabłonków Incident).

On 26 August, Hitler tried to dissuade the British and the French from interfering in the upcoming conflict, even pledging that the Wehrmacht forces would be made available to Britain's empire in the future. The negotiations convinced Hitler that there was little chance the Western Allies would declare war on Germany, and even if they did, because of the lack of "territorial guarantees" to Poland, they would be willing to negotiate a compromise favourable to Germany after its conquest of Poland. Meanwhile, the number of increased overflights by high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft and cross border troop movements signalled that war was imminent.

On 29 August, prompted by the British, Germany issued one last diplomatic offer, with Fall Weiss "Case White" yet to be rescheduled. That evening, the German government responded in a communication that it aimed not only for the restoration of Danzig but also the Polish Corridor (which had not previously been part of Hitler’s demands) in addition to the safeguarding of the German minority in Poland. It said that they were willing to commence negotiations, but indicated that a Polish representative with the power to sign an agreement had to arrive in Berlin the next day while in the meantime it would draw up a set of proposals. The British Cabinet was pleased that negotiations had been agreed to but, mindful of howEmil Hacha had been forced to sign his country away under similar circumstances just months earlier, regarded the requirement for an immediate arrival of a Polish representative with full signing powers as an unacceptable ultimatum. On the night of 30/31 August, German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop read a 16-point German proposal to the British ambassador. When the ambassador requested a copy of the proposals for transmission to the Polish government Ribbentrop refused on the grounds that the requested Polish representative had failed to arrive by midnight. When Polish Ambassador Lipski went to see Ribbentrop later on 31 August to indicate that Poland was favorably disposed to negotiations, he announced that he did not have the full power to sign, and Ribbentrop dismissed him. It was then broadcast that Poland had rejected Germany's offer, and negotiations with Poland came to an end. Hitler issued orders for the invasion to commence soon afterwards.

On 29 August, German saboteurs planted a bomb at the railway station in Tarnów and killed 21 passengers, leaving 35 wounded.

On 30 August, the Polish Navy sent its destroyer flotilla to Britain, executing Operation Peking. On the same day, Marshal of Poland Edward Rydz-Śmigły announced the mobilization of Polish troops. However, he was pressured into revoking the order by the French, who apparently still hoped for a diplomatic settlement, failing to realize that the Germans were fully mobilized and concentrated at the Polish border. During the night of 31 August, the Gleiwitz incident, a false flag attack on the radio station, was staged near the border city of Gleiwitz by German units posing as Polish troops, inUpper Silesia as part of the wider Operation Himmler. On 31 August 1939, Hitler ordered hostilities against Poland to start at 4:45 the next morning. Because of the prior stoppage, Poland managed to mobilize only 70% of its planned forces, and many units were still forming or moving to their designated frontline positions.

Opposing forces

Germany[]

Germany had a substantial numerical advantage over Poland and had developed a significant military prior to the conflict. The Heer (army) had some 2,400 tanks organized into six panzer divisions, utilizing a new operational doctrine. It held that these divisions should act in coordination with other elements of the military, punching holes in the enemy line and isolating selected units, which would be encircled and destroyed. This would be followed up by less-mobile mechanized infantry and foot soldiers. The Luftwaffe (air force) provided both tactical and strategic air power, particularly dive bombers that disrupted lines of supply and communications. Together, the so-called "new" methods, were nicknamed "Blitzkrieg" (lightning war). Historian Basil Liddell Hart claimed "Poland was a full demonstration of the Blitzkrieg theory." Some other historians, however, disagree.

Aircraft played a major role in the campaign. Bombers also attacked cities, causing huge losses amongst the civilian population through terror bombing. The Luftwaffe forces consisted of 1,180 fighters, 290 Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers, 1,100 conventional bombers (mainly Heinkel He 111s and Dornier Do 17s), and an assortment of 550 transport and 350 reconnaissance aircraft. In total, Germany had close to 4,000 aircraft, most of them modern. A force of 2,315 aircraft was assigned to Weiss. Due to its prior participation in the Spanish Civil War, the Luftwaffe was probably the most experienced, best trained and best equipped air force in the world in 1939.

Poland

Between 1936 and 1939, Poland invested heavily in the Central Industrial Region. Preparations for a defensive war with Germany were ongoing for many years, but most plans assumed fighting would not begin before 1942. To raise funds for industrial development, Poland sold much of the modern equipment it produced. In 1936, a

Polish Infantry

National Defence Fund was set up to collect funds necessary for strengthening the Polish Armed forces. The Polish Army had approximately a million soldiers, but less than ½ of them were mobilized by 1 September. Latecomers sustained significant casualties when public transport became targets of the Luftwaffe. The Polish military had fewer armored forces than the Germans, and these units, dispersed within the infantry, were unable to effectively engage the enemy.

Experiences in the Polish-Soviet War shaped Polish Army organizational and operational doctrine. Unlike the trench warfare of World War I, the Polish-Soviet War was a conflict in which the cavalry's mobility played a decisive role. Poland acknowledged the benefits of mobility but was unable to invest heavily in many of the expensive, unproven inventions since then. In spite of this, Polish cavalry brigades were used as a mobile mounted infantry and had some successes against both German infantry and cavalry.

Polish PZL.37 Łoś medium bomber

The Polish Air Force (Lotnictwo Wojskowe) was at a severe disadvantage against the German Luftwaffe, although it was not destroyed on the ground early on, as is commonly believed. The Polish Air Force lacked modern fighters, but its pilots were among the world's best trained, as proven a year later in the Battle of Britain, in which the Poles played a major part.

Overall, the Germans enjoyed numerical and qualitative aircraft superiority. Poland had only about 600 aircraft, of which only 37 P-37 Łoś bombers were modern and comparable to its German counterparts. The Polish Air Force had roughly 185 PZL P.11 and some 95 PZL P.7 fighters, 175 PZL.23 Karaś Bs, 35 Karaś As, and by September, over 100 PZL.37s were produced. However, for the September Campaign, only some 70% of those aircraft were mobilized. Only 36 PZL.37s were deployed. All those aircraft were of indigenous Polish design, with the bombers being more modern than fighters, according to the Ludomił Rayski air force expansion plan, which relied on a strong bomber force. The Polish fighters were a generation older than their German counterparts; the PZL P.11 fighter—produced in the early 1930s—had a top speed of only 365 km/h (227 mph), far less than German bombers. To compensate, the pilots relied on its maneuverability and high diving speed.

Polish 7TP light tank

The tank force consisted of two armored brigades, four independent tank battalions and some 30 companies of TKS tankettes attached to infantry divisions and cavalry brigades. A standard tank of the Polish Army during the Polish Defensive War of 1939 was the 7TP light tank. It was the first tank in the world to be equipped with a diesel engine and 360° Gundlach periscope. The 7TP was significantly better armed than its most common opponents, the GermanPanzer I and II, but only 140 tanks were produced between 1935 and the outbreak of the war. Poland had also a few relatively modern imported designs, such as 50 Renault R35 tanks and 38 Vickers E tanks.

The Polish Navy was a small fleet of destroyers, submarines and smaller support vessels. Most Polish surface units followed Operation Peking, leaving Polish ports on 20 August and escaping by way of the North Sea to join with the British Royal Navy. Submarine forces participated in Operation Worek, with the goal of engaging and damaging German shipping in the Baltic Sea, but they had much less success. In addition, many merchant marine ships joined the British merchant fleet and took part in wartime convoys.

Phoney War / Battle from September 1939-May 1940

The Phoney War was a phase early in World War II—in the months following Britain and France's declaration of war on Germany (shortly after the German invasion of Poland) in September 1939 and preceding the Battle of France in May 1940—that was marked by a lack of major military operations in Continental Europe. The various European powers had declared war on one another but neither side had committed to launching a significant land offensive, notwithstanding the terms of the Anglo-Polish military alliance and the Franco-Polish military alliance, which obliged the United Kingdom and France to assist Poland.

The period was also called at the time, the Twilight War by Winston Churchill, der Sitzkrieg in German ("the sitting war": a play on the wordBlitzkrieg), the Bore War (a play on the Boer War), the Polish dziwna wojna ("strange war"), and the French drôle de guerre("strange/funny war"). The American news magazine TIME called the period the Lullablitz.

The term Phoney War was possibly coined by U.S. Senator William Borah who stated in September 1939, "There is something phoney about this war."

Inactivity

While most of the German army was engaged in Poland, a much smaller German force manned the Siegfried Line, their fortified defensive line along the French border. At the Maginot Line on the other side of the border, British and French troops stood facing them, but there were only some local, minor skirmishes. The Royal Air Force dropped propaganda leaflets on Germany and the first Canadian troops stepped ashore in Britain, while

People of Warsaw under British Embassy in Warsaw with banner "Long live England!" just after British declaration of state of war with Nazi Germany

western Europe was in a strange calm for seven months. Meanwhile, the opposing nations clashed in the Norwegian Campaign. In their hurry to re-arm, Britain and France had both begun buying large amounts of weapons from manufacturers in the U.S. at the outbreak of hostilities, supplementing their own productions. The non-belligerent U.S. contributed to the Western Allies by discounted sales, and, later, lend-lease of military equipment and supplies.

Despite the relative calm on land, on the high seas the war was very real indeed. Within a few hours of the declaration of war, the British liner Athenia was torpedoed off the Hebrides with the loss of 112 lives in what was to be the beginning of the long running Battle of the Atlantic. On 4 September, the Allies announced a blockade of Germany to prevent her importing food and raw materials to sustain her war effort, and the Germans immediately declared a counter-blockade.

At the Nuremberg Trials, Alfred Jodl said that "if we did not collapse already in the year 1939 that was due only to the fact that during the Polish campaign, the approximately 110 French and British divisions in the West were held completely inactive against the 23 German divisions."

Saar Offensive

The Saar Offensive was a French operation into Saarland on the German 1st Army defence sector in the early stages of World War II. The purpose of the attack was to assist Poland, which was then under attack. However, the assault was stopped and the French forces withdrew.

According to the Franco-Polish military convention, the French Army was to start preparations for the major offensive three days after mobilisation started. The French forces were to effectively gain control over the area between the French border and the German lines and were to probe the German defenses. On the 15th day of the mobilization (that is on 16 September), the French Army was to start a full-scale assault on Germany. The preemptive mobilization was started in France on August 26 and on September 1 full mobilization was declared.

French mobilization suffered from an inherently out of date system. The French military′s ordnance lacked the tanks and planes of the mechanized German military which greatly affected their ability to swiftly deploy their forces on the field, French command still believed in tactics of the previous war which relied heavily on stationary artillery which took time to transport and deploy (many pieces also had to be retrieved from storage before any advance could be made).

A French offensive in the Rhine valley began on 7 September, four days after France declared war on Germany. Then, the Wehrmacht was occupied in the attack on Poland, and the French soldiers enjoyed a decisive numerical advantage along the border with Germany. However, the French did not take any action that was able to assist the Poles. Eleven French divisions advanced along a 32 km (20 mi) line near Saarbrückenagainst weak German opposition. The French army had advanced to a depth of 8 km (5.0 mi) and captured about 20 villages evacuated by the German army, without any resistance. However, the half-hearted offensive was halted after France seized the Warndt Forest, 3 sq mi (7.8 km2) of heavily-mined German territory.

The attack did not result in any diversion of German troops. The all-out assault was to be carried out by roughly 40 divisions, including one armored division, three mechanized divisions, 78 artillery regiments and 40 tank battalions. On 12 September, the Anglo French Supreme War Council gathered for the first time at Abbeville in France. It was decided that all offensive actions were to be halted immediately. General Maurice Gamelinordered his troops to stop "not closer than 1 kilometre" from the German positions along the Siegfried Line. Poland was not notified of this decision. Instead, Gamelin informed Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły that 1/2 of his divisions were in contact with the enemy, and that French advances had forced the Wehrmachtto withdraw at least six divisions from Poland. The following day, the commander of the French Military Mission to Poland—General Louis Faury—informed the Polish chief of staff—General Wacław Stachiewicz—that the planned major offensive on the western front had to be postponed from 17 September to 20 September. At the same time, French divisions were ordered to retreat to their barracks along the Maginot Line. The Phoney War had begun.

Winter War

The Winter War (Finnish: Talvisota, Swedish: Vinterkriget, Russian: Зимняя война (trans. Zimnyaya voyna) was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet offensive on 30 November 1939 – three months after the start of World War II and the Soviet invasion of Poland – and ended on 13 March 1940 with the Moscow Peace Treaty. The League of Nations deemed the attack illegal and expelled the Soviet

A Finnish machine gun crew during the Winter War

Union from the League on 14 December 1939.

The Soviet forces had three times as many soldiers as the Finns, 30 times as many aircraft, and a hundred times as many tanks. The Red Army, however, had been crippled by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin's Great Purge of 1937, reducing the army's morale and efficiency shortly before the outbreak of the fighting. With more than 30,000 of its army officers executed or imprisoned, including most of those of the highest ranks, the Red Army in 1939 had many inexperienced senior officers. Because of these factors, and high commitment and morale in the Finnish forces, Finland was able to resist the Soviet invasion for far longer than the Soviets expected.

Hostilities ceased in March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland ceded 11% of its pre-war territory and 30% of its economic assets to the Soviet Union. Soviet losses on the front were heavy, and the country's international reputation suffered. The Soviet forces did not accomplish their objective of the total conquest of Finland, but did gain sufficient territory along Lake Ladoga to provide a buffer for Leningrad. The Finns, however, retained their sovereignty and enhanced their international reputation.

The peace treaty thwarted the Franco-British plan to send troops to Finland through northern Scandinavia. One of the Allied operation's major goals had been to take control of northern Sweden's iron ore and cut its deliveries to Germany.

Battle of Tolvajärvi

Prelude: After the Winter War broke out on November 30, the Finnish troops north of Lake Ladoga began a pre-planned retreat before the overwhelming opposition. It was not thought possible for the Soviets to deploy large number of troops in this rugged and almost roadless area, but the Soviets deployed an entire division which advanced along the road between Suojärvi and Tolvajärvi (now Tolvayarvi, Russia). The Soviet advance was a serious threat to the Finnish IV Corps' lines of communication. To counter this threat the Finnish high command assembled "Group Talvela" commanded by Colonel Paavo Talvela.

Battle: The northern group consisting of two battalions soon met Soviet resistance. In fact, they met the Soviet 718th regiment which was preparing to make its own attack on the Finnish flank. By noon, the Finnish troops withdrew to their own lines. Although this attack was a failure, it prevented the 718th from attacking the Finnish flank, and also from sending reinforcements to the south.

While the second battalion of the Finnish 16th infantry regiment (II/JR 16) was preparing to attack along the road it was interrupted by an attack from the Soviet 609th regiment. The Finns were still able to attack after they got some artillery support. The Finnish attack continued towards a hotel located on a thin isthmus between the two lakes. Pajari decided to commit his reserves in a pincer attack at the Soviet troops around the hotel. In the end the hotel was captured and in it were found a dead Soviet regimental commander and all the regiment's papers.

The Finns withdrew back over the lakes for the night. In the morning Colonel Talvela demanded a new attack and the 139th division was pushed back and later (20–22 December) destroyed aroundÄgläjärvi (now, Yaglyayarvi) (some 20 km from Tolvajärvi). Contact was also made with the 75th Soviet division which was sent as reinforcements.

Battle of Suomussalmi[]

{C}On November 30, 1939, the Soviet 163rd division crossed the border between Finland and the Soviet Union and advanced from the north-east towards the village of Suomussalmi. The Soviet objective was to advance to the city of Oulu, effectively cutting Finland in half. This sector had only one Finnish battalion (Er.P 15), which was placed near Raate, outside Suomussalmi.

Suomussalmi was taken with little resistance on December 7 (only two incomplete companies of covering forces led a holding action between the border and Suomussalmi), but the Finns destroyed the village before this, to deny the Soviets shelter, and withdrew to the opposite shore of lakes Niskanselkä and Haukiperä.

The first extensive fight started on December 8, when Soviet forces began to attack across the frozen lakes to the west. Their attempt failed completely. The second part of Soviet forces led the attack to the northwest on Puolanka, that was defended by the Er.P 16 (lit. 16th detached battalion), that had just arrived. This attempt also failed.

On December 9, the defenders were reinforced with a newly founded regiment (JR 27). Colonel Hjalmar Siilasvuo was given the command of the Finnish forces and he began immediate counter-measures to regain Suomussalmi. The main forces advanced on Suomussalmi, but failed to take the village, suffering serious losses.

On December 24, Soviet units counterattacked, but failed to break through the surrounding Finnish forces.

Reinforced with two new regiments (JR 64 and JR 65), the Finns again attacked on December 27. This time, they took the village, and the Soviets retreated in panic over the surrounding frozen lakes.

During this time, the Soviet 44th Division (mostly composed of Ukrainians) had advanced from the east towards Suomussalmi. It was entrenched on the road between Suomussalmi and Raate and got caught up in the retreat of the other Soviet forces.

Between January 4 and January 8, 1940, the 44th Division was divided into isolated groups and destroyed by the Finnish troops (in a tactic known as motti), leaving much heavy equipment for the Finnish troops.

Battle of Changsha

The Japanese launched the attacks on September 17, when their forces in northern Jiangxi attacked westward toward Hunan. However, the Japanese stretched too far out westward and were counter-attacked by Chinese forces from the south and the north, forcing them to retreat eastward.

On September 19, the Japanese then proceeded to attack the Chinese along the Sinchiang River. Even though the use of poison gas was prohibited by the Geneva Protocol, the Japanese army employed it on Chinese positions. On September 23 the Japanese drove the Chinese out of the Sinchiang river area, and the 6th and 13th Divisions crossed the river under artillery cover and advanced further south along the Miluo River.

Heavy fighting continued after the 23rd and the Chinese retreated southward to attract the Japanese while supporting battalions arrived on the east and the west for encirclement maneuver. On September 29 the Japanese reached the outskirts of Changsha. However, they were unable to conquer the city because their supply lines were cut off by the Chinese. By October 6 the Japanese forces at Changsha were decimated while the remnants retreated northward.

Battle of the River Plate[]

On 13 December, the ships sighted each other and closed. Admiral Graf Spee—despite having correctly identified Exeter—initially suspected that the two light cruisers were smaller destroyers and that the British ships were protecting a merchant convoy, the destruction of which would be a major prize. Since Graf Spee′s reconnaissance aircraft was out of service, Langsdorf relied on lookouts for this information. He decided to engage, despite having received a broadly accurate report from the German naval staff on 4 December outlining British activity in the River Plate area. This report included information that Ajax, Achilles, Exeter and Cumberland were patrolling the South American coast. Langsdorf realised too late that he was facing three cruisers. Calling upon the immediate acceleration of his diesel engines, he closed the enemy squadron at 24 kn (28 mph; 44 km/h) in the hope of engaging the steam-driven British ships before they could work up from cruising speed to full power.This strategy may seem an inexplicable blunder. Langsdorf could perhaps have manoeuvered to keep the British ships at a range where he could destroy them with his 11 in (280 mm) guns while remaining out of the effective range of their smaller 6- and 8-inch guns. On the other hand, he knew the British cruisers had a 4–6 kn (4.6–6.9 mph; 7.4–11 km/h) speed advantage over Graf Spee and could in principle stay out of range should they choose to do so—standard cruiser tactics in the presence of a superior force—while calling on reinforcements.

The British executed their battle plan: Exeter turned north-west, while Ajax and Achilles—operating together—turned north-east to spread Graf Spee′s fire.Graf Spee opened fire on Exeter at 19,000 yd (17,000 m) with her six 11 in (280 mm) guns at 06:18. Exeter opened fire at 06:20, Achilles at 06:21, Exeter′s aft guns at 06:22 and Ajax at 06:23. From her opening salvo, Graf Spee′s gunfire proved fairly accurate, her third salvo straddling Exeter. At 06:23, an 11 in (280 mm) shell burst just short of Exeter, abreast the middle of the ship. Splinters from this shell killed the torpedo tubes' crews, damaged the ship's communications, riddled the ship's funnels and searchlights and wrecked the ship's Walrus aircraft just as it was to be launched for gunnery spotting. Three minutes later, Exeter suffered a direct hit in her "B"-turret, putting it and its two guns out of action.[7] Shrapnel swept the bridge, killing or wounding all bridge personnel except the captain and two others. Captain Bell's communications were wrecked. Communications from the aft conning position were also destroyed, and the ship had to be steered via a chain of messengers for the rest of the battle.

Meanwhile, Ajax and Achilles closed to 13,000 yd (12,000 m) and started making in front of Graf Spee, causing her to split her main armament at 06:30, and otherwise use her 5.9 in (150 mm) guns against them. At 06:32, Exeter fired two torpedoes from her starboard tubes but both missed. At 06:37, Ajaxlaunched her spotter aircraft from its catapult. At 06:38, Exeter turned so that she could fire her port torpedoes, and received two more direct hits from 11 in (280 mm) shells. One hit "A"-turret and put it out of action, the other entered the hull and started fires. At this point Exeter was severely damaged, having only "Y"-turret still in action, a 7°list, was being flooded and being steered with the use of her small boat's compass. In return, one of Exeter′s 8 in (200 mm) shells penetrated two decks, then exploded in Graf Spee′s funnel area — destroying her raw fuel processing system and leaving her with just 16 hours fuel, insufficient to allow her to return home.

Thus, from 06:38, Graf Spee was doomed; she could not make the fuel system repairs (of this complexity) under fire. Two-thirds of her anti-aircraft guns were knocked out as well as one of her secondary turrets. There were no friendly naval bases within reach. She was not seaworthy and could only make the neutral port of Montevideo.

At approximately 06:36, Admiral Graf Spee hauled around from an easterly course, now behind Ajax and Achilles, toward the northwest and laid smoke. This position brought Langsdorf roughly parallel to Exeter. By 06:50, Exeter listed heavily to starboard, taking water forward. Nevertheless, she still steamed at full speed and fired with her one remaining turret. Forty minutes later, water splashed in by an 11 in (280 mm) near-miss short-circuited Exeter′s electrical system for that turret. Captain Bell was forced to break off action. This would have been the opportunity to finish off Exeter. Instead, the combined fire of Ajax and Achilles drew Langsdorf's attention as both ships closed.

At 06:56, Ajax and Achilles turned to starboard to bring all their guns to bear, at 07:10 causing Admiral Graf Spee to turn away and lay a smokescreen. At 07:10, the two light cruisers turned to reduce the range from 8 mi (7.0 nmi; 13 km), even though this meant only their forward guns could fire. At 07:16, Graf Spee turned to port and headed straight for the heavily damaged Exeter, but fire from Ajaxand Achilles forced her at 07:20 to turn and fire her 11 in (280 mm) guns at them, who turned to starboard to bring all their guns to bear. Ajax turned to starboard at 07:24 and fired her torpedoes at a range of 4.5 mi (3.9 nmi; 7.2 km), causing Graf Spee to turn away under a smokescreen. At 07:25, Ajax was hit by an 11 in (280 mm) shell that put "X"-turret out of action and jammed "Y"-turret, causing some casualties. By 07:40, Ajax and Achilles were running low on resources and the British decided to change tactics, moving to the east under a smokescreen. Harwood decided to shadowAdmiral Graf Spee and try to attack at night when he could attack with torpedoes and better utilise his advantage of speed and manoeuvrability while minimising his deficiencies in armour. Ajax was again hit by an 11 in (280 mm) shell that destroyed her mast and caused some casualties. Graf Spee continued on a south-westward course.

The Pursuit[]

The battle now turned into a pursuit. Captain Parry of Achilles wrote afterwards: 'To this day I do not know why the Admiral Graf Spee did not dispose of us in the Ajax and the Achilles as soon as she had finished with the Exeter. The British and New Zealander cruisers split up keeping about 15 mi (13 nmi; 24 km) from Graf Spee. Ajax kept to the German's port and the Achilles to the starboard. At 09:15, Ajax recovered her aircraft. At 09:46, Harwood signalled to the Cumberland for reinforcement, and the Admiralty also ordered ships within 3,000 mi (2,600 nmi; 4,800 km) to proceed to the River Plate. At 10:05, Achilles had overestimated Graf Spee′s speed, and she came into range of the German guns. Graf Spee turned and fired two three-gun salvoes with her foreguns. Achilles turned away under a smokescreen.

According to Pope, at 11:03 a merchant ship was sighted close to Graf Spee. After a few minutes, Graf Spee called Ajax on W/T using both ships' pre-war call-signs, with the signal: "please pick up lifeboats of English steamer". The German call-sign was DTGS, confirming to Harwood that the pocket-battleship he had engaged was indeed Graf Spee. Ajax did not reply but a little later the British flagship closed with SS Shakespeare with its lifeboats still hoisted and men still on board. Graf Spee had fired a gun and ordered them to stop, but when they did not obey orders to leave the ship Langsdorff decided to continue on his way, and Shakespeare had a lucky escape. The shadowing continued for the rest of the day until 19:15, when Graf Spee turned and opened fire on Ajax, which turned away under a smokescreen.

It was now clear that Graf Spee was entering the River Plate Estuary. Since the estuary had sandbanks, Harwood ordered the Achilles to shadow the Graf Spee while Ajax would cover any attempt to double back through a different channel. The sun set at 20:48, with Graf Spee silhouetted against the sun. Achilles had again closed the range and Graf Spee opened fire, forcing Achilles to turn away. During the battle, a total of 108 men had been killed on both sides, including 36 on Graf Spee.

Graf Spee entered Montevideo in neutral Uruguay, dropping anchor at about 00:10 on 14 December. This was a political error, since Uruguay, while neutral, had benefited from significant British influence during its development, and it favoured the Allies. The British Hospital, for example (where the wounded from the battle were taken) was the leading hospital in the city. The port of Mar del Plata on the Argentine coast and 200 mi (170 nmi; 320 km) south of Montevideo would have been a better choice for Graf Spee.

Also, had Graf Spee left port at this time, the damaged Ajax and Achilles would have been the only British warships that it would have encountered in the area.

Trap of Montevideo[]

In Montevideo, the 13th Hague Convention came into play. Under Article 12, "...belligerent war-ships are not permitted to remain in the ports, roadsteads, or territorial waters of the said Power for more than twenty-four hours...", modified by Article 14 "A belligerent war-ship may not prolong its stay in a neutral port beyond the permissible time except on account of damage..." British diplomats duly pressed for the speedy departure of the Graf Spee. Also relevant was Article 16, of which part reads, "A belligerent war-ship may not leave a neutral port or roadstead until twenty-four hours after the departure of a merchant ship flying the flag of its adversary."

The Germans released 61 captive British merchant seamen who had been on board in accordance with their obligations. Langsdorff then asked the Uruguayan government for two weeks to make repairs. Initially, the British diplomats in Uruguay—principally Eugen Millington-Drake—tried to have Admiral Graf Speeforced to leave port immediately. After consultation with London, which was aware that there were no significant British naval forces in the area, Millington-Drake continued to openly demand that Graf Spee leave. At the same time, the British secretly arranged for British and French merchant ships to steam from Montevideo at intervals of 24 hours, whether they had originally intended to do so or not, thus invoking Article 16. This kept Graf Spee in port and allowed more time for British forces to reach the area.

At the same time, efforts were made by the British to feed false intelligence to the Germans that an overwhelming British force was being assembled, including Force H (the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal and the battlecruiser HMS Renown), when in fact only the heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland was nearby. Cumberland—one of the earlier County class cruisers—was only a little more powerful thanExeter, with two more 8 in (200 mm) guns. She was no match alone for Admiral Graf Spee, whose guns had much longer range and fired much heavier shells. Cumberland arrived at 22:00 on 14 December, after steaming at full speed for 36 hours from the Falkland Islands. Overwhelming British forces (HMS Renown, Ark Royal, Shropshire, Dorsetshire, and Neptune) were en route, but would not assemble until 19 December. For the time being, the total force comprised the undamaged Cumberland, and the damaged Ajax and Achilles. To reinforce the propaganda effect, these ships—which were waiting just outside the 3 mi (2.6 nmi; 4.8 km) limit—were ordered to make smoke, which could be clearly seen from the Montevideo waterfront.

The Germans, however, were entirely deceived, and expected to face a far-superior force on leaving the River Plate. Graf Spee had also used two-thirds of her 11 in (280 mm) ammunition and only had enough left for approximately a further 20 minutes of firing, which was hardly enough to fight her way out of Montevideo, let alone get back to Germany.

While the ship was prevented from leaving the harbour, Captain Langsdorff consulted with his command in Germany. He received orders that permitted some options, but not internment in Uruguay. The Germans feared that Uruguay could be persuaded to join the Allied cause. Ultimately, he chose to scuttle his ship in the River Plate estuary on 17 December, to avoid unnecessary loss of life for no particular military advantage, a decision that is said to have infuriated Adolf Hitler. The crew of Admiral Graf Spee was taken to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where Captain Langsdorff committed suicide on 19 December. He was buried there with full military honours, and several British officers who were present attended. Many of the crew members were reported to have moved to Montevideo with the help of local people of German origin. The German dead were buried in the "Cementerio del Norte" in Montevideo.

Battle of the Atlantic (Skimishes in 1939)[]

In 1939, the Kriegsmarine lacked the strength to challenge the combined British Royal Navy and French Navy (Marine Nationale) for command of the sea. Instead, German naval strategy relied oncommerce raiding using capital ships, armed merchant cruisers, submarines and aircraft. Many German warships were already at sea when war was declared, including most of the available U-boats and the "pocket battleships" (Panzerschiffen) Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee which had sortied into the Atlantic in August. These ships immediately attacked British and French shipping. U-30sank the liner SS Athenia within hours of the declaration of war—in breach of her orders not to sink passenger ships. The U-boat fleet, which was to dominate so much of the Battle of the Atlantic, was small at the beginning of the war; many of the 57 available U-boats were the small and short-range Type IIs, useful primarily for minelaying and operations in British coastal waters. Much of the early German anti-shipping activity involved minelaying by destroyers, aircraft and U-boats off British ports.

With the outbreak of war, the British and French immediately began a blockade of Germany, although this had little immediate effect on German industry. The Royal Navy quickly introduced a convoy system for the protection of trade that gradually extended out from the British Isles, eventually reaching as far as Panama, Bombay and Singapore. Convoys allowed the Royal Navy to concentrate its escorts near the one place the U-boats were guaranteed to be found — the convoys. Each convoy consisted of between 30 and 70 mostly unarmed merchant ships.

Some British naval officials, particularly the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, sought a more 'offensive' strategy. The Royal Navy formed anti-submarine hunting groups based on aircraft carriers to patrol the shipping lanes in the Western Approaches and hunt for German U-boats. This strategy was deeply flawed because a U-boat, with its tiny silhouette, was always likely to spot the surface warships and submerge long before it was sighted. The carrier aircraft were little help. Although they could spot submarines on the surface, at this stage of the war they had no adequate weapons to attack them. Any submarine found by an aircraft was long gone by the time surface warships arrived. The hunting group strategy proved a disaster within days. On September 14 1939, Britain's most modern carrier, HMS Ark Royal, narrowly avoided being sunk when three torpedoes from U-39 exploded prematurely. U-39 was promptly forced to surface and scuttle by the escorting destroyers, becoming the first U-boat loss of the war. The British failed to learn the lesson: another carrier, HMS Courageous, was sunk three days later by U-29.

Escort destroyers hunting for U-boats continued to be a prominent, but misguided, feature of British anti-submarine strategy for the first year of the war. U-boats nearly always proved elusive, and the convoys, denuded of cover, were put at even greater risk.

German success in sinking Courageous was surpassed a month later when Günther Prien in U-47 penetrated the British base at Scapa Flow and sank the old battleship HMS Royal Oak at anchor. Prien immediately became a hero in Germany.

In the South Atlantic, British forces were stretched by the cruise of Admiral Graf Spee, which sank nine merchant ships of 50,000 tons in the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans during the first three months of war. The British and French formed a series of hunting groups including three battlecruisers, three aircraft carriers, and 15 cruisers to seek the raider and her sister Deutschland, which was operating in the North Atlantic. These hunting groups had no success until Graf Spee was caught off the mouth of the River Plate by an inferior British force. After suffering damage in the subsequent action, she took shelter in neutral Montevideo harbour and was scuttled on 17 December 1939.

War from 1940 (May)-1941 (January)[]

Battle of Atlantic (Skimishes in 1940)[]

After this initial burst of activity, the Atlantic campaign quieted down. Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander of the U-boat fleet, had planned a maximum submarine effort for the first month of the war, with almost all the available U-boats out on patrol in September. That level of deployment could not be sustained; the boats needed to return to harbour to refuel, re-arm, re-stock supplies, and refit. The harsh winter of 1939–40, which froze over many of the Baltic ports, seriously hampered the German offensive by trapping several new U-boats in the ice. Hitler's plans to invade Norway and Denmark in the spring of 1940 led to the withdrawal of the fleet's surface warships and most of the ocean-going U-boats for fleet operations in Operation Weserübung.

The resulting Norwegian campaign revealed serious flaws in the magnetic influence pistol (firing mechanism) of the U-boats' principal weapon, the torpedo. Although the narrow fjords gave U-boats little room for manoeuver, the concentration of British warships, troopships and supply ships provided countless opportunities for the U-boats to attack. Time and again, U-boat captains tracked British targets and fired, only to watch the ships sail on unharmed as the torpedoes exploded prematurely (due to the influence pistol), or hit and failed to explode (because of a faulty contact pistol), or ran beneath the target without exploding (due to the influence feature or depth control not working correctly). Not a single British warship was sunk by a U-boat in more than 20 attacks. As the news spread through the U-boat fleet, it began to undermine morale. The director in charge of torpedo development continued to claim it was the crews' fault. In early 1942, the problems were determined to be due to differences in magnetic fields at high latitudes[16][page needed] and a slow leakage of high-pressure air from the submarine into the torpedo's depth regulation gear. Eventually those problems were solved by about March 1941, allowing the torpedos to become a formidable weapon.

Winter War (1940)[]

Battle Kollaa[]

The Battle of Kollaa was fought from December 7, 1939 - March 13, 1940 in the Ladoga's Karelia, Finland as a part of the Winter War.

Despite having far fewer troops than the Soviets, the Finnish forces (12th division) repelled the Red Army because the Soviets were only prepared to proceed along roads. The Kollaa area had very few roads, all of them guarded by Finnish troops, and the Soviets were not able to proceed cross-country without skis.

Kollaa is often considered to have been one of the most difficult places to defend during the Winter War. It has been estimated that the Red Army fired almost 40,000 artillery rounds at the defence line during a single day, whereas the Finnish Artillery could fire only 1,000 rounds per day at the very best.

Although they stopped the Red Army, the 12th Division suffered heavy losses, with the Battle of Kollaa continuing until the end of the Winter War. The Red Army managed to penetrate the Finnish defence line in Kollaa several times, thus pushing the Finns out of their positions but the Finns systematically counter-attacked to restore the integrity of their defence line. The Finnish defence came close to a collapse at the very end of the war - in fact, the Soviets managed to form a 0,5 - 1,5 kilometers deep fracture point into the Finnish defense line on March 12. As a result, the commander of the 12th division of the Finnish Army considered abandoning the main defence line at Kollaa, but as the news from the sector were that the situation was "not yet that alarming", the commander ordered a counter-attack and the defence line to be retaken the following day. However, as the information of the concluded peace treaty reached the front, those orders were cancelled and the men were told to hold their current positions until the end of hostilities.

A memorable quote from the Battle of Kollaa is Major General Hägglund's question, "Will Kollaa hold? (Kestääkö Kollaa)", to which Lieutenant Aarne Juutilainen replied, "Kollaa will hold (Kollaa kestää), unless the orders are to run."

The legendary sniper Simo Häyhä served in the Kollaa front.

Battle of Honkaniemi[]

On the nights of February 25 and 26, members of the Jaeger Battalion 3 were carried by trucks to Heponotko, which was about 3 km away from a depot in Honkaniemi (now Lebedevka) then they skied to the starting point at 4:00 am. The tank company arrived around 30 minutes later from a 50 km march. That march, however, cost them more than they would have liked. Since the conditions of the weather and road were extremely bad, the tank company lost 5 of their 13Vickers 6-Ton tanks mostly due to engine failures.

Seeing this as a major blow to their offensive capabilities, Captain Kunnas split his remaining tanks between the 2nd and 3rd Jaegers Companies and the 1st Jaegers Company. Six tanks will support the Jaegers while two will help the 1st secure the left flank. It was chosen that the attack would commence at 5:00 am, but the communication with the artillery battalions failed so it was decided that they would try again at 6:15 am.

When communications with the artillery battalions were up and running, the time had come to attack. However another setback had occurred. During the preliminary artillery barrage, some of the shells landed at the starting point, resulting in the 30 Finns being killed or injured. The attack had to be postponed by another hour.

The Beginning[]

After the initial artillery bombardment by the two artillery battalions (the 1st Battalions of the 21st and 5th Artillery Regiments) the attack commenced. However, the Finns had had another set-back, another two tanks had been lost to technical failures thereby reducing the total Finnish Tanks to only six for the entire battle. Even after all those set-backs, there was more to come. The 1st Jaegers Battalion had advanced some 200 meters before having to halt under the tremendous firing powers of the Red Army. The 1st Jaegers Company which was covering the left flank, advanced foreword towards the railroad only to be unable to cross it. The 2nd and 3rd Jaegers Companies, which were the main attack forces, had advanced to 200 meters SW from the rail road, but had to be stopped.

Tank Backup[]

The 4th Armoured Company had one of the worst days ever. One of its Vickers tanks got stuck in a ditch; the turret was damaged in the process and it had to retreat back to the starting point. The remaining five tanks were lost in a more honourable way, "being targeted by T-26s, T-28s and the 45 mm AT guns".

The platoon commander's tank, Lt.V. Mikkola's, advanced the farthest, almost 500 meters, almost into Soviet areas. Only two Finnish tanks were able to destroy other Soviet tanks, the tank of Corporal E. Seppälä, which had kept on fighting after being immobilized, had taken out two Soviet tanks before the crew had to abandon their vehicle. The other tank was commanded by 2nd Lt. J. Virniö, which had destroyed one tank before being damaged.

Finnish Retreat[]

Captain Kunnas received orders at 10:00 pm that he was to abort the attack and retreat. The Finns' first tank battle met with an unsuccessful end. The entire tank battle had been fought with inexperienced crews and almost no radio communication, since the tanks had been bought from the UK without guns, optics and radios, and some even without the driver's seat, in order to save money. Due to the lack of vital equipment, communication between tanks was impossible and the tanks would act upon their own judgement.

Battle of France - May 10-June 25, 1940[]

In the Second World War, the Battle of France was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, beginning on 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), German armoured units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and surround the Allied units that had advanced into Belgium. During the fighting, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and many French soldiers were evacuated from Dunkirk in Operation Dynamo.

In the second operation, Fall Rot (Case Red), executed from 5 June, German forces outflanked the Maginot Line and pushed deep into France.Italy declared war on France on 10 June and soon afterwards the French government fled to Bordeaux. France's capital of Paris was occupied on 14 June. On 17 June, Philippe Pétain publicly announced France would ask for an armistice. On 22 June, an armistice was signed between France and Germany, going into effect on 25 June. For the Axis Powers, the campaign was a spectacular victory.

Following the Battle of Britain, France was divided into a German occupation zone in the north and west, a small Italian occupation zone in the southeast, and an unoccupied zone, the zone libre, in the south. A rump state, Vichy France, administered all three zones according to the terms laid out in the armistice. In November 1942, the Axis forces also occupied the zone libre, and metropolitan France remained under Axis occupation until after the Allied landings in 1944. The Low Countries remained under German occupation until 1944 and 1945.

Northern Front[]

Germany initiated Fall Gelb on the evening prior to and the night of 10 May. During the late evening of 9 May, German forces occupied Luxembourg. Army Group B launched its feint offensive during the night into the Netherlands and Belgium. During the morning of 10 May, Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) from the 7th Flieger and 22. Luftlande Infanteriedivision under Kurt Student executed surprise landings at The Hague, on the road to Rotterdam and against the Belgian fort at Eben-Emael in order to facilitate Army Group B's advance.

The French command reacted immediately, sending its 1st Army Group north in accordance with Plan D. This move committed their best forces, diminishing their fighting power by the partial disorganisation it caused and their mobility by depleting their fuel stocks. By the time the French 7th Army crossed the Dutch border, they found the Dutch already in full retreat, and withdrew into Belgium to protect Brussels.

The Netherlands[]

The Luftwaffe was guaranteed air superiority over the Netherlands by sheer numerical superiority. They allocated 247 medium bombers, 147 fighter aircraft, 424 Junkers Ju 52 transports, and 12 Heinkel He 59 seaplanes to operations over the Netherlands. The Dutch Air Force, the Militaire Luchtvaartafdeling(ML), had a strength of 144 combat aircraft, half of which were destroyed within the first day of operations. The remainder was dispersed and accounted for only a handful of Luftwaffe aircraft shot down. In total the ML flew a mere 332 sorties, losing 110 of its aircraft.

The German 18. Armee secured all the strategically vital bridges in and toward Rotterdam, which penetrated Fortress Holland and bypassed the New Water Line from the south. However, an operation organised separately by the Luftwaffe to seize the Dutch seat of government, known as the Battle for The Hague, ended in complete failure. The airfields surrounding the city (Ypenburg, Ockenburg, and Valkenburg) were taken with heavy casualties and transport aircraft losses. Some 96 aircraft in all were lost to Dutch shell fire. The Luftwaffe''s Transportgruppen operations had cost it 125 Ju 52s destroyed and 47 damaged, representing 50% of the fleet's strength. Moreover, the airborne operation had cost the German paratroopers 4,000 men, of whom 1,200 wereprisoners of war, out of 8,000. The Dutch evacuated them back to Britain. The total percentage cost of the defeat was 20% of NCOs and men and 42% of German officers were lost.

The French 7th Army failed to block the German armoured reinforcements from the 9. Panzerdivision, which reached Rotterdam on 13 May. That same day in the east, following the Battle of the Grebbeberg in which a Dutch counter-offensive to contain a German breach had failed, the Dutch retreated from the Grebbe line to the New Water Line. The Dutch Army, still largely intact, surrendered in the evening of 14 May after the Bombing of Rotterdam by the Luftwaffe. Heinkel He 111 medium bombers of Kampfgeschwader 54 (Bomber Wing 54) destroyed the centre of the city, an act which has remained controversial. The Dutch Army considered its strategic situation to have become hopeless and feared further destruction of the major Dutch cities. The capitulation document was signed on 15 May. However, Dutch forces continued fighting in Zeeland and the colonies while Queen Wilhelmina established a government in exile in Britain. Dutch casualties amounted to 2,157 army, 75 air force, and 125 Navy personnel. 2,559 civilians were also killed.

Invasion of Belgium

The Germans were able to establish air superiority in Belgium. Having completed thorough photographic reconnaissance missions, they destroyed 83 of the 179 aircraft of the Aeronautique Militaire within the first 24 hours. The Belgians would fly 77 operational missions but would contribute little to the air campaign. The Luftwaffe was assured air superiority over the Low Countries.

Because Army Group B had been so weakened compared to the earlier plans, the feint offensive by the German 6. Armee was in danger of stalling immediately, since the Belgian defences on the Albert Canal position were very strong. The main approach route was blocked by Fort Eben-Emael, a large fortress then generally considered the most modern in Europe, controlling the junction of the Meuse and the Albert Canal. Any delay might endanger the outcome of the entire campaign, because it was essential that the main body of Allied troops was engaged before Army Group A established bridgeheads. To overcome this difficulty, the Germans resorted to unconventional means in the assault on the fort. In the early hours of 10 May, DFS 230gliders landed near the fort and unloaded assault teams that disabled the main gun cupolas with hollow charges. The bridges over the canal were seized by German paratroopers. The Belgians launched considerable counter attacks which were broken up by the Luftwaffe. Shocked by a breach in its defences just where they had seemed the strongest, the Belgian Supreme Command withdrew its divisions to the KW-line five days earlier than planned. Similar operations against the bridges in the Netherlands, at Maastricht, failed. All were blown up by the Dutch and only one railway bridge was taken. This stalled the German armour on Dutch territory for a time.

The BEF and the French First Army were not yet entrenched, and the news of the defeat on the Belgian border was unwelcome. The Allies had been convinced Belgian reistance would have given them several weeks to prepare a defensive line at the Gembloux Gap. When General Erich Hoepner's XVI Panzerkorps, consisting of 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions, was launched over the newly-captured bridges in the direction of the Gembloux Gap, this seemed to confirm the expectations of the French Supreme Command that the German Schwerpunkt would be at that point. Gembloux was located between Wavre and Namur, on flat, ideal tank terrain. It was also an unfortified part of the Allied line. In order to gain time to dig in there, René Prioux, commanding the Cavalry Corps of the French 1st Army, sent two French Light Mechanised divisions, the 2nd DLM and 3rd DLM, forward to meet the German armour at Hannut, east of Gembloux. They would provide an advanced guarding screen which would stall the Germans and allow sufficient time for the French 1st Army to dig into formidable positions.

Battle of Hannut and Gembloux

The resulting Battle of Hannut, which took place on 12-13 May, was the largest tank battle until that date, with about 1,500 armoured fighting vehicles participating. The French disabled about 160 German tanks for the loss of 91 Hotchkiss H35 and 30 Somua S35 tanks destroyed or captured. The Germans controlled the battlefield after a voluntary French withdrawal. They recovered and eventually repaired or rebuilt many of their knocked-out tanks so German irreparable losses amounted to just 49 tanks (20, 3rd Panzer and 29, 4th Panzer). Prioux had achieved his mission in stalling the Panzers and allowing the French 1st Army to settle, so it was a tactical victory for the French. By contrast, although Hoepner had succeeded in diverting the French First Army from Sedan, which was his most important mission, he failed to destroy or forestall it. The French would escape the encirclement and still render invaluable support to the British Army in Dunkirk just two weeks later.

On 14 May, having been tactically defeated at Hannut, Hoepner tried to break the French line again, against orders, leading to The Battle of the Gembloux Gap. This was the only time in the campaign when German armour frontally attacked a strongly held fortified position. The attempt was repelled by the 1st Moroccan Infantry Division, costing 4. Panzerdivision another 42 tanks, 26 of which were irreparable. This French defensive success was made irrelevant by events further south. Following the battle with the French 1st Army on 15 May, the war diary of the 4. Panzerdivisionnoted irreparable losses that day of nine Panzer Is, nine Panzer IIs, six Panzer IIIs, eight Panzer IVs, and two command tanks; of an original total of 314. 137 machines, of which 20 were mk IIIs and four were mk IVs, remained combat-ready.

Central Front[]

Belgian and French Ardennes[]

In the centre, the progress of German Army Group A was to be delayed by Belgian motorised infantry and French mechanised cavalry divisions (Divisions Légères de Cavalerie) advancing into the Ardennes. The main resistance came from the Belgian 1st Chasseurs Ardennais along with the 5th French Light Cavalry Division (DLC). These forces had insufficient anti-tank capacity to block the surprisingly large number of German tanks they encountered and quickly gave way, withdrawing behind the Meuse. The German advance was greatly hampered by the sheer number of troops trying to force their way along the poor road network. Kleist′s Panzergruppe had more than 41,000 vehicles. This huge armada had been allocated only four march routes through the Ardennes. The time-tables proved to be wildly optimistic and there was soon heavy congestion, beginning well over the Rhine to the east, which would last for almost two weeks. This made Army Group A very vulnerable to French air attacks, but these did not materialise. Although Gamelin was well aware of the situation, the French bomber force was far too weak to challenge German air superiority so close to the German border. The French had tried in vain to stem the flow of the German armour during the Battle of Maastricht, and failed with heavy losses. In two days, the bomber force had been reduced to 72 out of 135.

On 11 May, Gamelin had ordered reserve divisions to begin reinforcing the Meuse sector. Because of the danger the Luftwaffe posed, movement over the rail network was limited to night-time, slowing the reinforcement, but the French felt no sense of urgency as they believed the build-up of German divisions would be correspondingly slow. The French Army did not conduct river crossings unless assured of heavy artillery support. While they were aware that the German tank and infantry formations were strong, they were confident in their strong fortifications and artillery superiority. However, the quality of the fighting men was dubious. The German advance forces reached the Meuse line late in the afternoon of 12 May. To allow each of the three armies of Army Group A to cross, three major bridgeheads were to be established at: Sedan in the south, Monthermé to the northwest and Dinant further to the north. The first German units to arrive hardly had local numerical superiority; their already insufficient artillery support was further limited by an average supply of just 12 rounds per gun. Fortunately for the German divisions, the French artillery was also limited to a daily combat supply rate of 30 rounds per "tube" (gun).

Battle of Sedan

At Sedan, the Meuse Line consisted of a strong defensive belt 6 km (3.7 mi) deep, laid out according to the modern principles of zone defence on slopes overlooking the Meuse valley and strengthened by 103 pillboxes, manned by the 147th Fortress Infantry Regiment. The deeper positions were held by the 55th Infantry Division. This was only a grade "B" reserve division. On the morning of 13 May, the 71st Infantry Divisionwas inserted to the east of Sedan, allowing 55th Infantry to narrow its front by one-third and deepen its position to over 10 km (6.2 mi). Furthermore, it had a superiority in artillery to the German units present.

On 13 May, the German XIX Korps forced three crossings near Sedan, executed by the 1., 2. and 10. Panzerdivisions, reinforced by the eliteGroßdeutschland infantry regiment. Instead of slowly massing artillery as the French expected, the Germans concentrated most of their air power (as they lacked strong artillery forces) to smash a hole in a narrow sector of the French lines by carpet bombing and by dive bombing.Hermann Göring had promised Guderian that there would be extraordinarily heavy air support during a continual eight hour air attack, from 08:00am until dusk. The Luftwaffe executed the heaviest air bombardment the world had yet witnessed and the most intense by the Germans during the war. The Luftwaffe committed two Sturzkampfgeschwader (Dive Bomber Wings) to the assault, flying 300 sorties against French positions. A total of 3,940 sorties were flown by nine Kampfgeschwader (Bomber Wings).

Some of the forward pillboxes were unaffected, and repulsed the crossing attempts of the 2. and 10. Panzerdivisions. However, it transpired the morale of the deeper units of the 55th Infantry had been broken by the impact of the air attacks. The French supporting artillery batteries had fled. At a cost of a few hundred casualties, the German infantry had penetrated up to 8 km (5.0 mi) into the French defensive zone by midnight. Even by then, most of the infantry had not crossed, much of the success being due to the actions of just six platoons, mainly assault engineers.

The disorder that had begun at Sedan spread down the French lines. At 19:00 on 13 May, the 295th regiment of 55th Infantry Division, holding the last prepared defensive line at the Bulson ridge 10 km (6.2 mi) behind the river, was panicked by the false rumour that German tanks were already behind its positions. It fled, creating a gap in the French defences, before even a single German tank had crossed the river. This "Panic of Bulson" also involved the divisional artillery. The Germans had not attacked their position, and would not do so until 12 hours later, at 07:20 on 14 May. Still, the French had several hours to launch a counter offensive before the Germans consolidated the bridgeheads, but failed to attack soon enough.

Recognising the gravity of the defeat at Sedan, General Gaston-Henri Billotte, commander of the 1st Army Group, whose right flank pivoted on Sedan, urged that the bridges across the Meuse be destroyed by air attack, convinced that "over them will pass either victory or defeat!". That day, every available Allied light bomber was employed in an attempt to destroy the three bridges, but failed to hit them while suffering heavy losses. Some 44% of the Allies' bomber strength was destroyed.

Collapse of the Meuse front

Heinz Guderian, the commander of the German XIX. Armeekorps, had indicated on 12 May that he wanted to enlarge the bridgehead to at least 20 km (12 mi). His superior, Ewald von Kleist, ordered him on behalf of Hitler to limit his moves to a maximum of 8 km (5.0 mi) before consolidation. At 11:45 on 14 May, von Rundstedt confirmed this order, which implied that the tanks should now start to dig in. Guderian was able to get to Ewald von Kleist to agree to "reconnaissance in force", by threatening to resign and behind the scenes interventions. This vague terminology allowed Guderian to move forward, effectively ignoring Ewald von Kleist's order to halt.

In the original von Manstein Plan as Guderian had suggested, secondary attacks would be carried out to the southeast, in the rear of the Maginot Line, to confuse the French command. This element had been removed by Halder but Guderian now sent the 10th Panzerdivision andGroßdeutschland infantry regiment south to execute precisely such a feint attack, using the only available route south over the Stonneplateau. The commander of the French 2nd Army, General Charles Huntziger, intended to carry out a counterattack at the same spot by the armoured 3e Division Cuirassée de Réserve (DCR) to eliminate the bridgehead. This resulted in an armoured collision, both parties trying in vain to gain ground in furious attacks from 15-17 May, the village of Stonne changing hands many times. Huntzinger considered this at least a defensive success and limited his efforts to protecting his flank. Holding Stonne and taking Bulson would have enabled the French to hold onto the high ground overlooking Sedan. They could disrupt the Sedan bridgehead, even if they could not take it. Heavy battles took place and Stonne changed hands 17 times. However, on the evening of 17 May, it fell to the Germans for the last time.

Meanwhile, Guderian had turned his other two armoured divisions, the 1. and 2. Panzerdivisions, sharply to the west on 14 May. They began to advance at speed to the English Channel.

On 15 May, in heavy fighting, Guderian's motorised infantry dispersed the reinforcements of the newly formed French 6th Army in their assembly area west of Sedan, undercutting the southern flank of the French 9th Army. The 9th Army collapsed, and surrendered en masse. The 102nd Fortress Division, its flanks unsupported, was surrounded and destroyed on 15 May at the Monthermébridgehead by the 6. and 8. Panzerdivisions acting without air support. The French 2nd Army had also been seriously mauled and had rendered itself impotent. The 9th Army was giving way because they also did not have time to fortify their lines. Erwin Rommel had breached its defences within 24 hours of its conception. This allowed the impetuous Rommel to break free with his 7.Panzerdivision, refusing to allow his division rest and advancing both by day and night. The Ghost division advanced 30 mi (48 km) in just 24 hours.